- Home

- Steve Fletcher

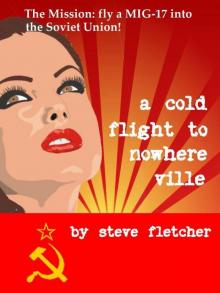

A Cold Flight To Nowhereville

A Cold Flight To Nowhereville Read online

A COLD FLIGHT TO NOWHEREVILLE

By Steve Fletcher

Copyright © 2011 by Steve Fletcher

Groom Lake, Nevada

September 1956

The official name for the site was “Watertown.” But there was neither water nor town at GroomLake.

It was an alkali flat in the desolate, rolling desert terrain of Nevada, surrounded by reddish, sandy dirt thick with coarse sage. Nestled in what had once been known as EmigrantValley between the Groom and Papoose mountains, the area surrounding the dry lakebed was characterized by blistering heat and uniquely inhospitable living conditions that had earned the site the tongue-in-cheek name ‘Paradise Ranch.’ Many things the site was, all of them highly classified, but a paradise it wasn’t. The area had seen some silver mining operations in the middle to late 1800s, a particularly notorious murder around 1897, and had been fading quietly into the dust of history when an Army airstrip was built beside the alkali flat during the Second World War. That had been abandoned in 1945 and once again the area was forgotten until a Beech Bonanza flew low overhead sometime in 1955. In the aircraft had been some personages of particular import: Kelly Johnson, head of Lockheed’s classified Skunkworks department; his test pilot, Tony Levier; Dick Bissell, director of the CIA’s U2 program; and Bissell’s military deputy, Ozzie Ritland. GroomLake was chosen as the site for a new classified base and airstrip for precisely the reasons that had served to keep it an unremarkable footnote to history: its remote location and brutally inhospitable climate. That summer, construction began on three hangars, an airstrip, a control tower and a mess hall.

Air Force Major John Hardin stood on the tarmac in front of a large, open hangar, shielding his eyes from the sun as he watched an aircraft approaching the runway on short final. He was a man of medium height, his hair short and brown, ‘high and tight’ over his ears, and the eyes fixed on the fuselage of the approaching jet analyzed it with a pilot’s precision. He wore a drab flight suit and was perspiring in Groom Lake’s afternoon heat. Climates in his career, he reflected, had been a matter of feast or famine: baking in the Nevada sun or freezing in Korea. He had flown with the 39th Squadron during the war, rotating over in the summer of 1952 just as the squadron’s venerable P-51s had been upgraded to the F-86 Sabre Jet. And he acquitted himself well flying combat air patrols in the aptly named MiG Alley, where the Yalu River emptied into the Yellow Seas. He’d splashed five MiG-15s before the war ended, and gun camera footage from one of his dogfights was still being shown in flight school. In the years that followed Hardin had built a reputation as a superior pilot, serving as flight instructor in the F-86 and newer F-100 before being selected for the test pilot program and sent to Watertown. The progress of his career had been gratifying, and his ego had kept pace with his rank. But there were times he missed the glories and stark terrors of combat.

Peacetime was a bitch. Who had said that?

As he stood on the ramp watching the fighter on approach, two other men appeared from the hangar bay, walking out onto the ramp to meet the jet. Recognizing them as two of the many Skunkworks technicians assigned to Watertown, he surveyed them briefly and paid them no further attention. The runway extended roughly north to south, the northern end jutting just into the boundary of the dry lakebed occupying virtually the entire expanse of desert north of the installation. There were two other hangars bordering the ramp, both to Major Hardin’s left; to his right stood a couple of Butler buildings and some temporary trailers. There wasn’t much else at Watertown. But those buildings, especially the hangars, housed aircraft of a type that demanded absolute secrecy. For providing that Watertown was a hard place to beat.

Towards the south end of the runway the fighter’s rubber tires struck the pavement with a smoky screech and the jet streaked past hangar 18, the turbojet engine whining as it gradually slowed from around 150 knots to taxi speed. At the distant northern end of the runway the jet turned onto the taxi ramp and the pilot throttled up a bit, approaching the hangar. Hardin saw him slide the glass canopy back to let some air into the cockpit. An untrained observer might have confused the aircraft with an F-86…but not for long. Like the F-86, this aircraft had swept wings, a semi-monocoque fuselage and a yawning air intake that comprised the entire nose of the plane, but those were the only external similarities between the two aircraft. It was obviously smaller than the F-86; the idle whine of this turbojet was different, it didn’t sound like the F-86’s General Electric J-73. The wings were located midway up on the fuselage, higher than the F-86; the tail was wrong, it was too big, and the horizontal stab was located too high.

A trained observer would have recognized it instantly as a Soviet MiG-17 Fresco, a remarkable specimen and virtually brand new.

One of the Skunkworks techs smirked as the jet taxied to a stop and the high-pitched whine of the Klimov turbine spooled down to silence. “It’s still got the Egyptian markings.”

“You guys need to get rid of those,” Hardin said sharply.

“We’ll paint over them when Bob tells us to,” the other tech replied, moving to chock the jet’s wheels. Hardin scowled at the comment but let it pass. He bridled at the casual attitudes of the Skunkworks crew, but being civilians there wasn’t much he could do about it. At the moment Lockheed still ostensibly ran this place.

The young lieutenant piloting the MiG removed his flight helmet and stepped out of the cockpit onto the short ladder the technicians leaned against the fuselage. “John Wesley Hardin!” the pilot sang out with a broad grin.

“No relation, dickhead,” he called back. He’d gotten plenty of ribbing about his name and the similarity it bore to the notorious murderer of the 1870s. That one had gunned down an impressive number of people between Texas and Abilene, Kansas before drawing a prison sentence and eventually getting shot. Major John Hardin had killed people as well but, having had the good sense to do it in an F-86 during the war, avoided his namesake’s fate. The combination of that experience and his notorious predecessor, however, had been sufficient to land him the handle ‘Shooter,’ and it had stuck.

But his middle name was Robert, not Wesley. He didn’t think anyone knew that, though.

“Nice little jet,” First Lieutenant Mark Lucas announced, climbing down onto the ramp and grinning as the techs moved around the MiG, giving it a thorough post-flight inspection and preparing it for maintenance, “handles great. They’ve fixed the high-G problem the 15 had.”

“I hope you didn’t pull more than four.” According to the data the spooks had come up with, the MiG-17 should have been able to handle seven Gs or better. But this airplane had just arrived at Watertown the week before and the test pilots didn’t have permission for high-G maneuvering yet. The MiG-17 Fresco’s immediate forebear, the MiG-15 Fagot, had demonstrated some alarming handling characteristics: a bad high-speed snake and a tendency to depart controlled flight during high-G maneuvers. The CIA had acquired two of the older jets, now parked in the hangar behind him, and Hardin had experienced this tendency quite by accident one day when he had unwittingly managed to throw the MiG into a flat spin at 15,000 feet above the desert. After a heart stopping few seconds he had been able to push the nose over and recover without going into a stall, but it had been an experience he didn’t wish to repeat. Now it was the responsibility of the test group at Watertown to gather data on its flight characteristics and determine whether or not Mikoyan-Gurevich had copied their design flaws over to the MiG-17.

Lucas pulled his flight helmet off. “No,” he responded, a little more soberly, “but I did pull four.”

“You’re too heavy on the damn stick,” Hardin told him, suspecting his subordinate was fudging the numbers a little. “

Use less stick and more forehead. This bird can probably pull more G’s than you can and if you go to sleep and auger in I’m going to shoot you myself.”

It was easy to recognize traits in Lucas that he himself had experienced trouble with over the years. Did that make it disingenuous to get after him?

Self-examination was a characteristic of weakness, done by people that failed at life. He didn’t fail, not ever. He’d gotten his undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering from Georgetown, and he’d made his grades without even trying. He’d entered the military, flown fighters in Korea, and his abilities had enabled him to excel. There weren’t many pilots better in a dogfight that he was. He seemed to know instinctively which direction his opponent was going to turn, whether the MiG was about to go high or low, and plan his intercept accordingly; he hadn’t really needed to pay more than cursory attention to the intel briefs on tactics. He knew he was smarter than the guy trying to shoot him down. He was smarter than the guy trying to teach him things.

But on his performance evals there was a phrase that tended to recur: less stick, more forehead. Think more. Plan better. He never paid much attention to that because his successes inherently argued against it. If he hadn’t been so successful then sure, it might be a valid point. But it obviously wasn’t.

Right?

It was oddly disconcerting to see a trait in his subordinate that seemed familiar. Better to drag Mark’s ass for it and then put the matter out of his mind.

“I’m not going to crash it,” the younger man replied with an overconfident smirk.

If he did, Hardin mused, he’d be giving him a big fat I-don’t-know-you at the board of inquiry.

A third technician appeared in the hangar bay. “Hey, Shooter! You’re wanted in ops.”

He turned, irritated. A small group of VIPs had flown in that morning on the C-47 Gooney Bird parked in front of Hangar Two and probably wanted a briefing on the new acquisition. He didn’t feel like giving one and headed back into the hangar bay, intending to get himself a cup of coffee from pre-flight. “That way,” the tech said obviously, jerking a thumb toward a trailer to the left of the hangar, “not this way.”

“I know which way ops is,” he shot back, his irritation showing. The tech grinned at his compatriots working around the MiG. “Shooter” Hardin’s ego was the stuff of legend, and it was common for him to make a group wait until he felt like giving a briefing.

In the pre-flight briefing room inside the hangar bay he took a paper cup, splashed coffee into it, and headed in no great hurry out of the hangar and across the short stretch of desert to the ops trailer. Giving briefings to visiting firemen represented a couple hours of unbearable tedium and he wasn’t looking forward to this one.

The trailer was hot, as one would expect a metal structure exposed to the merciless Nevada sun to be, and a window air conditioner was doing its best to alleviate the heat. A few oscillating fans were busily moving the air around as he stepped inside. Around a small conference table he saw a number of faces, most unfamiliar, conversing over coffee cups and several photos scattered haphazardly about. For a second or two he amused himself by trying to figure out their origins by their clothing. At one end of the table, in a folding metal chair, sat a slender graying man in a short-sleeved white shirt, pressed, t-shirt underneath, expensive-looking tie, gold tie-tac. Cup of coffee nearby, cream and sugar. While not physically imposing, there was a presence about the man that signified someone of power and access. CIA. The Company had been known to show up once in a while. Next to him, a couple more men in short-sleeved white shirts who looked as though they didn’t belong in them, ironed their clothes with rocks, no ties. Skunkworks techs. He knew these two, they weren’t assigned to Watertown but they were often around. Next to them sat a heavy, balding army Colonel with his olive-drab uniform jacket off, perspiration staining his shirt, a bottle of Nesbitt orange soda on the table before him. Redstone Arsenal. Army guy, rocket research. What’s he doing here? At the other side of the table sat Bob Davis, a former Marine pilot now employed by Skunkworks as the director of operations at Watertown and ostensibly his boss. Beside him sat a naval Captain, the cap sitting before him on the table festooned with scrambled eggs. He wasn’t a large man and had flight wings pinned above the significant fruit salad at his left breast pocket. Some kind of high-ranking former pilot with combat time according to his ribbons—and unless he was wrong, those two were the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign and World War Two Victory medals. His origins and purpose for being here Hardin could not guess at.

This wasn’t looking exactly like the typical VIP briefing. And why was Redstone here?

“Sit down, John,” Davis urged. “I don’t think you know Jim Weiss.” No further introduction was offered. “Colonel Sal Donaldson from Redstone. Barry Frank and Howard Frantz from Lockheed. Captain Bill Holveck from the Navy.”

Hardin nodded as he sat in the open chair by the navy Captain, placing his coffee cup on the table. He’d heard of Sal Donaldson but had not met him before. It wasn’t unusual to dispense with a good deal of the formalities in these situations. All kinds of strange government groups showed up out here.

“If you’d permit, Major,” Weiss began, “we’d like you to tell us a bit about your father.”

Hardin frowned. Now this was definitely not shaping up like a VIP briefing. “My father? Okay. Robert Hardin. I assume you’re referring to his duty with the Red Cross?”

Weiss nodded, seeming neither hostile nor friendly, merely intent. Possibly a little more on the unfriendly side. Chances were he already knew whatever he was about to be told. There was a definite tension in the air about the conference table.

“He served with the Red Cross in Russia, around 1917 to 1921, during the Bolshevik Revolution. Mainly around St. Petersburg, but I’m not sure exactly where all he was. He used to get a little vague about that part. Died about ten years ago.”

“Ty govorish po russki?Ty menya ponimayesh?” Weiss asked sharply, surprising him.

Did he speak Russian, did he understand? What was this? “Ya ploho govoryu po russki,” he responded, not really thinking. I do not speak Russian well. It wasn’t completely true. He’d grown up speaking Russian around his house as his father had been of the opinion that young John should have a second language.

“Kak tebya zovut? Rasskazhimne!” This sternly, a tone that brooked little argument.

Tell him my name? Suddenly he didn’t like this interview much, and he liked even less some CIA jackass ordering him around in Russian. “Otyebis,” he said rudely and almost immediately wished he hadn’t. He still hadn’t figured out who this character was.

But Weiss grinned broadly, shooting a knowing look at the Army colonel. “Yeah, he speaks the language. He told me to fuck off. But he speaks Russian with a Brooklyn accent, like he just walked in off the bowery. It’s about the damnedest thing I’ve ever heard.”

“I learned quite a bit from pop, but it’s been a while,” he said, feeling uncomfortable. But the tension in the atmosphere had eased considerably. ”What’s this about?”

“Actually your knowledge of your father’s movements is interesting,” Weiss remarked in a by-the-way tone. “We don’t know very much at all about what was happening in Russia during the Revolution and the Red Cross seems to develop selective amnesia when we ask them about it. But that’s not why we’re here and I apologize if I riled you a bit.”

“I’m not riled,” Hardin grumbled. “Yet.”

“Sal, why don’t you get us started?”

“What do you know of rockets?” Colonel Donaldson asked, taking a sip of his soda, his attention directed fully at Hardin.

He shrugged. “They go up. Other than that, not much.”

“Well,” the colonel continued, “we better do a bit of history then. Here’s the five-cent tour of World War Two: Hitler builds and launches the V-1 and V-2 rockets from a place called Peenemunde. The guy in charge is named von Braun.”

“He’s workin

g for us now, isn’t he?”

Donaldson nodded. “He is. He’s down in my part of the world. Peenemunde is on the Baltic coast, so the Soviets get there first and capture most of his staff. But von Braun, a Nazi general named…Dornberger, wasn’t it, Jim? Anyway, they and a few others managed to contact the 324th and surrender to them. Von Braun had been in some trouble with the SS so he didn’t much like his other options, and he wasn’t seeing a whole lot of difference between the SS and the Russians.”

“The way this has shaken out,” Weiss continued, “is that a lot of the Nazi research on guidance came over with Von Braun. But the Soviets got more of the booster stuff, so right now they’re about 10 years ahead of us on heavy-lift technology.”

“Heavy payloads,” Bob Davis explained.

“Thanks, Bob,” Hardin replied sarcastically. “I was having a hard time figuring out what ‘heavy-lift’ meant.”

“Where’s that one shot of the ground test at Baikonur?” Weiss glanced over the scattered photographs.

Howard Frantz, the Lockheed tech, had it. This was passed over to Hardin, who examined it curiously. He hadn’t flown the U2 mission that had taken this series of pictures of the Soviet Cosmodrome at Baikonur in Kazakhstan, but he knew who had. He’d been the guy’s instructor in flight school. The overflight program had just begin, there had been a couple of accidents with the U2 earlier in the year which had set the whole program back, but he’d hoped he would be selected for the first pilot class. He hadn’t. The first mission had gone to another of the test pilots and they’d flown out of Wiesbaden, Germany, not Watertown. He had been irked, and wondered if he was being prepped for the next U2 class. He’d never flown Kelly Johnson’s peculiar creation, administered under the code name ‘Aquatone,’ but badly wanted to. The aircraft’s primary payload was a large Hycon-B camera, capable of shooting high-resolution pictures of newsprint from thirteen miles up. Several of the craft were housed in hangars 2 and 3, long, slender glider-like aircraft, fantastically advanced, hideously expensive, capable of reaching altitudes of 70,000 feet and more. The things had an 80-foot wingspan and were powered by new Pratt & Whitney J-57’s, a type of turbojet that used a redesigned dual-rotor, axial flow compressor to lower fuel consumption. The things had an incredible range and could loiter over a target area for considerable periods of time. He’d heard it was possible, at the altitudes the U2 liked, to see the curvature of the earth and the blackness of space. But at those altitudes the performance envelope was extremely narrow and the J-57 had a tendency to flameout, requiring a steep dive to restart. The aircraft was also reported to be a problem to land, requiring the pilot to put it into a stall just to get it down into the runway.

A Cold Flight To Nowhereville

A Cold Flight To Nowhereville